The Village That Lives On Hope

“Every house in our village collapsed during the earthquake,” said Ram Sharan Parajuli. “It’s a miracle no one died.” We were standing at the spot where his home used to be, now reduced to mounds of stones and piles of wooden beams. “There used to be four houses here, but now it is all gone.”

The 24-year-old physics student had travelled from Kathmandu to his home for Dashain, the longest and most auspicious festival on the Nepali calendar. This year, along with the other villagers of Chimling Beshi, he was celebrating it in a temporary shelter. It seemed a bittersweet coincidence that Dashain – which celebrates the victory of good over evil – overlapped with the six month anniversary of the worst natural disaster to hit Nepal in 80 years.

We had set out for Sindhupalchok earlier that day on a bus packed with men, women and children wearing their best clothes, foreheads adorned with red tikas, on their way to visit relatives. Our overloaded bus climbed into the hills, swinging perilously around the corners of the twisting roads. The road journey felt dangerous, but when you look at the small, fragile houses on the hillside, many of them partially or completely destroyed, you realise that precariousness is a part of everyday life in this part of Nepal.

Chimling Beshi is one of many villages in Sindhupalchok district that was destroyed by the earthquake in April. Every house suffered severe damage and was rendered uninhabitable. The district suffered more devastation than any other, with around 3,500 deaths and nearly 64,000 houses – around 90 per cent –listed as ‘fully damaged’. The village is part of Mankha, the second most badly affected Village Development Committee in the district, where more than 7,500 people required immediate assistance after the earthquake. Six months after the earthquake, we were on our way to spend the night in the village, to see how life had changed for its inhabitants since the disaster.

This is the new settlement of Chimling Beshi. All the houses in this village were damaged in the earthquake. Photo: Ritu Panchal

AFTER WE CLIMBED a steep path from the nearby town of Khadichaur, rows of glinting metal roofs peeking out of lush foliage came into view. The small shacks were built by the villagers within a week of the earthquake, using materials salvaged from their ruined houses and bamboo from the forest.

“After the earthquake, the rainy season started and people were scared of landslides,” said Ram, as we navigated a steep path. “It was very hot and we had to carry large tin sheets two at a time from our old house.”

Below the six rows of tin houses stood three temporary school buildings for the younger children, built by NGOs shortly after the earthquake. Other than 25 kg of rice per household and some tin sheets, the villagers received little in the way of relief goods. It was difficult not to feel a sense of sadness at what had happened to this community. And yet, Chimling Beshi was full of life. Children were playing cards, elders were placing tikas onto the foreheads of their younger relatives, and the villagers had built a giant swing (called ping in Nepali) for Dashain.

But the scene was very different at the site of the old village, which stood a short trek away, on an adjacent hill. Within six months, the jungle had consumed what remained of the village. The trails were hidden under a blanket of moss and grass, and creepers and wild flowers grew on the broken walls of what used to be houses. It was hard to imagine that the same place was a thriving, sustainable community, and that these ruins used to be homes, which echoed with laughter. Babies were born here, elders had died here – but now nothing remained except for the ghost of a settlement.

In six months, nature has taken over the remains of the houses at the former site of the village of Chimling Beshi. Photo: Ritu Panchal

We clambered over rocks that had plunged down the hillside to reach four families who had decided to build temporary shelters next to the remains of their houses, rather than move. Weren’t they afraid of landslides?

“During the rainy season, I can’t sleep,” said Saraswoti Poudel. “But we didn’t want to leave our animals and our land.”

Their biggest concern was having better shelter, which was too costly for them to build on their own. The yearning for a proper home would become a familiar tale that we would hear again and again during our stay.

It was beginning to get dark as we made the hike back to the new village. That evening, Radha, Ram’s mother, prepared a meal of lentils, rice and potatoes for us, all gathered from the farmland. Subsistence farming has become more difficult since the family moved to the new location, as they now have to walk further to gather food from their land, which lies near their old home.

As we ate our meal outside the shelter, we began to shiver. The day and night time temperatures in Nepal fluctuate considerably. Earlier on, it had been searingly hot; but now, there was a harsh chill. We could only imagine how cold it might get in the winter, which was fast approaching. The tin sheets would provide little insulation to the villagers.

Inside the shelter, two chipped but sturdy double beds occupied most of the space, in addition to two cupboards and a dresser. A line of colourful clothes were hung up across one wall. We slept that night in thick blankets provided by our host, the blare of TV sets from the adjacent houses clearly audible.

THE NEXT MORNING, we woke early to the sounds of a village beginning to stir. The clatter of pots and pans, the clamour from the radio, and the smell of burning charcoal filled the air. We could see villagers occupied with their morning chores. Several of them were making their way down the tapering trail, towards their old settlement to tend to their land and animals, to pick vegetables. Many were making multiple trips to carry water home from a remote tap<

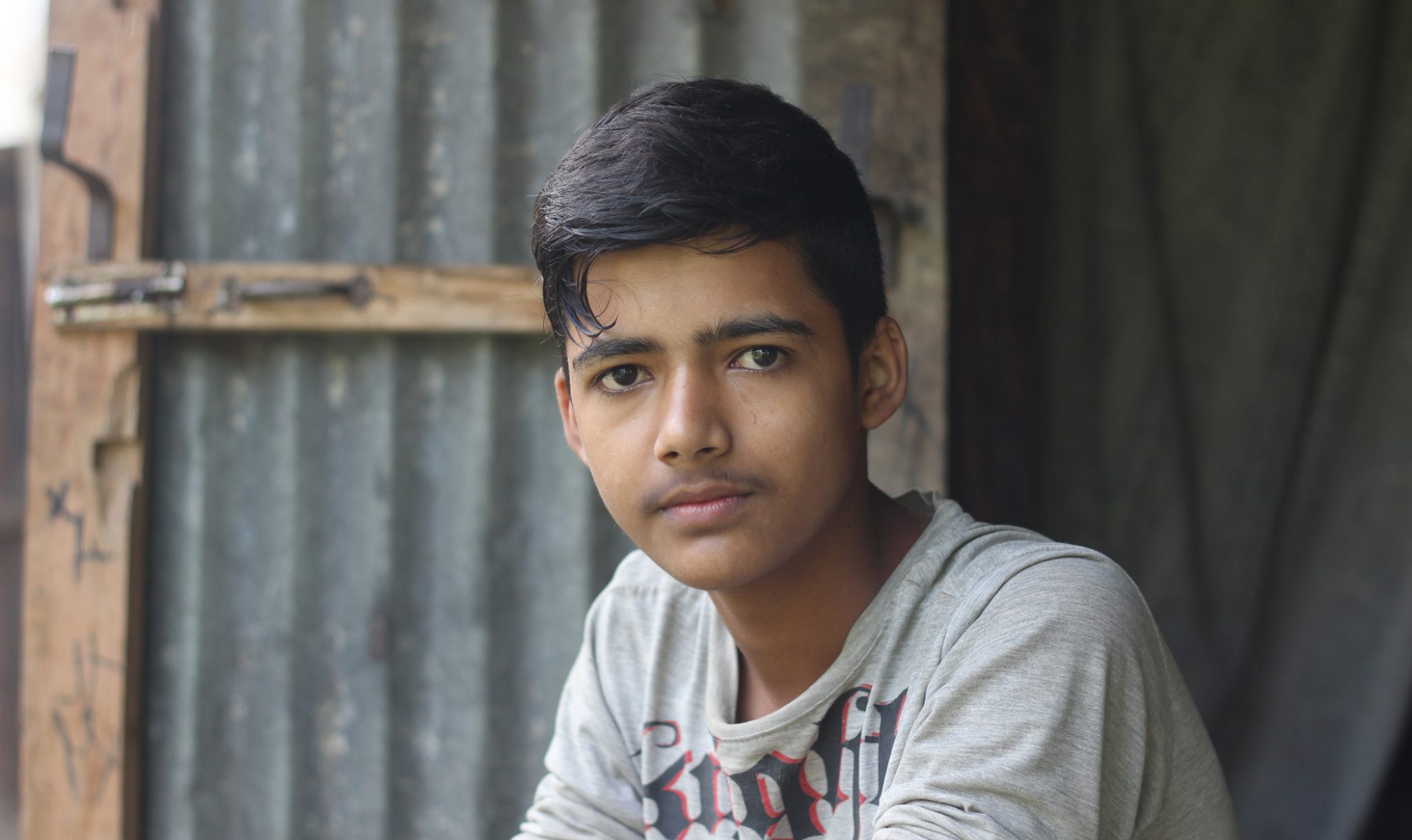

“We are compromising on even our basic needs,” said Nikesh Parajuli. “So building a house is a distant dream.” The 16-year-old’s biggest concern was that he found it difficult to study: being in cramped clusters, the settlement offered little space and he found it difficult to concentrate amidst all the noise. “I don’t even dare to hope for that here,” he said.

Nikesh Parajuli, a high school student, finds it difficult to find time or space to study in the temporary shelter. Photo: Naomi Mihara

Many villagers were hoping that their situation would be resolved soon. “For the time being, we don’t mind living here because it’s just temporary,” said Subash Battarai, a 21-year-old student, who had returned home for the festival>

How could they be sure, we wondered? “Hope is everything,” said Ram, simply.

Despite six months having passed, the villagers have no choice but to hold onto the promise made by the government back in April, of 200,000 Rs (around

When we broached the topic of politics, the sense of frustration was palpable. So far, households have only received 15,000 Rs (£95), a tiny fraction of the cost of rebuilding a house. One resident, Madan Krishna Adhikari, told us he had already spent that amount clearing the rubble of his old house.

“The government is not taking our problems seriously,” he said. “Even the plans of the earthquake-proof houses they proposed have not been released yet.” His biggest needs were getting basic construction materials, such as cement and iron rods, and the capital needed to build the house, he said.

Balkumari Parajuli and her granddaughter, Dikshika, who now lives in Kathmandu with her parents. Photo: Naomi Mihara

As we walked past the remains of another house, a sudden jolt shook the ground. A small girl ran past us into the arms of her grandmother, who had just emerged from a tin shack next to the rubble. It was the first time we had felt an aftershock in Nepal. But they occur frequently in this part, the villagers told us, providing a constant reminder that the next earthquake could happen anytime.

The elderly woman, Bal Kumari Parajuli, told us that before the earthquake her whole family had lived together in the house. But her son and daughter-in-law had decided to move with their young children to Kathmandu shortly afterwards. The children have returned to celebrate Dashain. But the earthquake and the destruction of her family home have traumatised Bal Kumari.Every morning she wakes up to the sight of her broken house, which is a perpetual reminder of what happened.

“I can’t sleep at night,” she said. “I miss my family and I am still worried about earthquakes.”

Like so many villages in Nepal, Chimling Beshi is a community in limbo, waiting for help that may or may not arrive so that they can rebuild their homes. Normality has been disrupted, but even these circumstances have become normal for the villagers now.

“Earthquakes come and go,” said Anant Kumari Adhikari, who allowed the other villagers to build their shelters on her land. “It has become like a habit.”