Nepal earthquake anniversary: between frustration and hope

For the past two days, Nepalis have held memorial services across the country to mark the first anniversary of the 2015 earthquake—24th April signals one year after the quake according to the Nepali calendar, and 25th April is one year after according to the Gregorian calendar used in the West. Whilst there were symbolic gestures such as lighting candles and laying wreaths by Prime Minister Khadga Prasad Oli, ordinary people voiced frustration with his government for the lack of progress in reconstruction efforts. Aftershock Nepal talked to a range of people during this emotionally wrought time, and many spoke with sadness of what they had lost. But there was also a sense of collective optimism and hope for the future.

‘It’s already been a year and the government has done nothing’

Story: Enika Rai

Photo: Enika Rai

“I am shocked. I came here to pray for everyone who lost their life during the earthquake. But they did not allow me to enter the event. Why? Because our prime minister came and normal people were not allowed in. Does our pray and condolence mean nothing compared to the prime minister? More so, it’s already been a year and the government has done nothing but do speeches at reconstruction events. I know that the youth of Nepal is ready to help out. At least I am ready to work for free for the earthquake victims.”

Suresh Dhungel | Maitighar Mandala

‘I work without break. But I am happy’

Story: Rupa Khadka, Sven Wolters

Photo: Sven Wolters

“I loved my house. I saved and invested everything into it. Sometimes I went without eating. But it collapsed. What can I do about it? Nothing. My husband works abroad, in Saudi Arabia. With the money he sends and a loan, I pay the workers to help me reconstruct my house. We use the rubble of the old one. It needs to be done as soon as possible because it’s almost monsoon season. So I work without break. But I am happy. At least all my children are with me. Many people lost their children and they have gone away. But this is my home. I love the nature and weather here. All the people I know live here. So do all my gods and goddesses. I will stay.”

Beemala Gandel | Kalyanpur

‘Now it is our turn to rebuild our culture. After every earthquake Nepal only becomes stronger’

Story: Sven Wolters

Photo: Sven Wolters

“I am proud to say that I’m born here, just around the corner from the monkey temple. Kathmandu is the cultural hub of the world. Today we came here to pray for the peace of the earthquake victims. But I am sure that soon these temples will be rebuilt. The older generation of artists are passing down their knowledge to the younger ones. Now it is our turn to rebuild our culture. After every earthquake Nepal only becomes stronger.”

Abinash Adhikari | Swayambhunath

‘It finally feels like we bicycle riders have a voice and we are ruling the street’

Story: Sven Wolters, Sameen Poudel

Photo: Sven Wolters

“I used to ride my motorbike everywhere. But the earthquake and the blockade afterwards stopped the fuel supply to Nepal. I started riding a bicycle instead. And even though I already broke my leg twice in accidents, I feel a lot stronger and healthier than I used to. And for the last eight months, I did not use a single litre of petrol. There’s more bicycle riders than last year and we are reducing the pollution levels. I am proud of myself and especially during this symbolic bike ride along the heritage sites today, it finally feels like we bicycle riders have a voice and we are ruling the street.”

Suraj Silwal | Patan Durbar Square

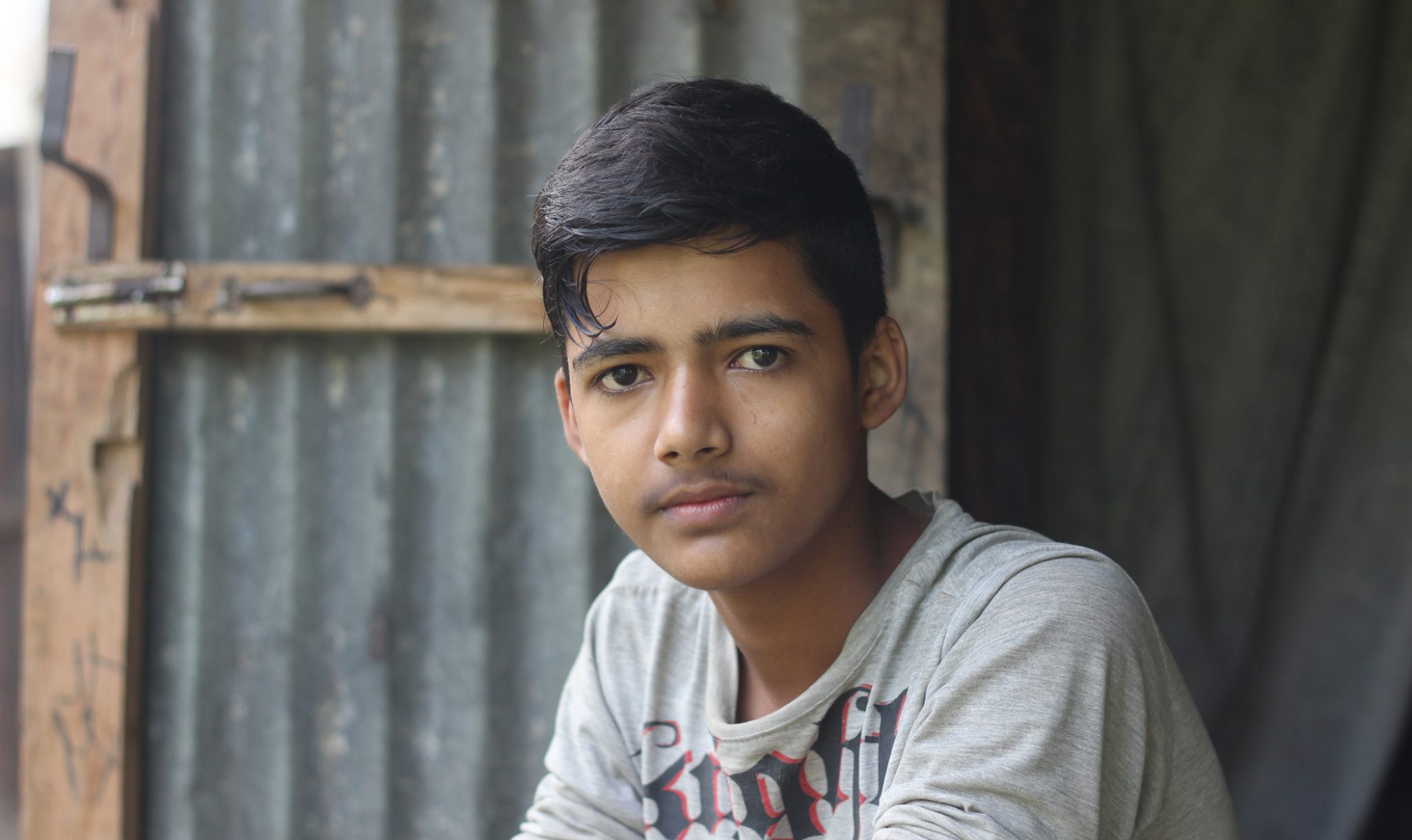

‘Sometimes I ask myself: “Why didn’t I just die in the earthquake?”’

Story: Enika Rai

Photo: Enika Rai

“All I ever got was one package of rice, one blanket and a tent, from an NGO. I didn’t get any relief money from the government and my name is not on any list for compensation of destroyed houses. But I did have a cottage. I built it all by myself, but it was on land owned by someone else. Now I have nothing and I have to work as a construction worker, for 600 rupees [approximately £3.8] a day. I can’t skip a day because I need to pay for food and school of my children. My son is six years old and my daughter is eight. Life is so hard. My children and me don’t have proper food, clothes and shelter. Sometimes I ask myself: “Why didn’t I just die in the earthquake?” But I have to live and be strong for my children’s sake.”

Mina Nepali | Nuwakot

‘Many people died. Since then business has been slow’

Story: Sven Wolters

Photo: Sven Wolters

“I ran out of my shop and looked back. It was scary. There was screaming everywhere. My mind was blank. I would never have thought that Dharahara could collapse. But then I saw it shaking from side to side, five times each side. Then it fell. Many people died. Since then business has been slow. There are a lot less Nepalese tourists here. But many more Westerners than before come by. To take a picture of the ruin.”

Pujan Bhakta Pradhan | Dharahara, Kathmandu

‘I am scared every day me and my family live in this house’

Story: Nitika Shrestha

Photo: Sven Wolters

“I am scared every day me and my family live in this house. It is only supported by teku [wooden poles] and there are cracks everywhere. But I don’t have any alternative. I am paying 5000 rupees rent for this whole house. Renting a single room in a safer place may cost me 3000 to 3500 rupees and with a family of seven I can’t afford that. I don’t know if I will get support from the government. Engineers inspected this house but they didn’t tell us anything. The landlord said that maybe next year they will start repairing it.”

Hari Krishna Shrestha | Patan

‘I stayed away from this place for five months’

Story: Sameen Poudel

Photo: Sameen Poudel

“Like every day I went here for my morning walk on the day of the earthquake. It was the most shocking experience I ever had. That is why I stayed away from this place for five months. Now I am retired and I come here again for my morning walk and to teach football to some youngsters and children in the evening. They call me guru ba [teacher]. I am a sports enthusiast and people need this public space for exercise. But these days I don’t see much people around here. That is why I call on the government to clear all the rubble from broken buildings they dumped here as soon as possible”

P D Tiwari | Tudikhel, Kathmandu

‘Kathmandu is a very high-speed city and we have all been working hard to restore it’

Story: Sven Wolters

Photo: Sven Wolters

“It’s very exciting to play cricket here at Thudikel. After the earthquake people came here for shelter but now we use it for leisure. It shows that one thing is for sure. Kathmandu is a very high-speed city and we have all been working hard to restore it. People who come to visit will not even realise any more that we have been through this national disaster.”

Ashwini Gupta | Tudikhel, Kathmandu

‘The charm of this place has gone with the earthquake’

Story: Pratik Rana

Photo: Sven Wolters

“The charm of this place has gone with the earthquake. I used to come here often and look at the temples before. But now for two days I have been working here to reconstruct the damage. This was the Khauma Dhwake [white gate]. There used to be meat offerings to the Gods here. It feels good to be working to reconstruct this site, it makes me happy. It is something that I can tell my children and my friends about.”

Kumari Birbal | Bhaktapur Durbar Square

‘We are trying to revive all the old technologies for earthquake resistance’

Story: Einar Thorsen

Photo: Pratik Rana

“I completed my architecture degree two years ago and I’m currently involved in an NGO that specialises in rural housing. The earthquake gave us an opportunity to learn about things we’ve previously only read in books, and we didn’t get a deep understanding of it—the real thing. After the earthquake we started to see the temples differently, we started to see the structural components differently. We are trying to revive all the old technologies for earthquake resistance. I’m quite disappointed with the government because we feel they have been delaying the reconstruction work. If we as even just a small NGO of 5-10 people can build houses and also 2,300 temporary shelters in such a short time, then why can’t the government? They have the expertise, they have the materials, but maybe they don’t believe in the traditional structures or they’re unsure which technology to follow. They should believe the traditional technology, because what has been built using traditional technology is still standing.”

Rakesh Maharjan | Bhaktapur Durbar Square

‘I might seem okay now, but every night I cry’

Story: Sven Wolters

Photo: Sven Wolters

“I got 50,000 rupees from the government to reconstruct my house. But I am old. So how can I do it all by myself? They told me that the money is for starting to build my house. But how can I afford to remove the rubble of my old house then? And if I don’t use the money as they say, they’ll take it back, they said. I don’t know what to do. I might seem okay now, but every night I cry. Because as soon as I got the money, my sons started fighting me in court about the land ownership.”

Ratna Kuwari Khadka | Singati

‘Me and my wife are still rebuilding houses for others’

Story: Pratik Rana

Photo: Pratik Rana

“It’s been a year now and me and my wife are still rebuilding houses for others, so that we can earn enough money to rebuild our own. But it’ll be another year or more before we can.”

Ram Bahadur Mazar | Bhaktapuq

‘Whenever I pass by my old home, my body shakes with fear’

Story: Mandira Dulal

Photo: Mandira Dulal

“I was about to close my eyes. Suddenly, my bed started shaking. At first, I didn’t know what was happening. Then I quickly picked up my phone and my laptop and I ran. The scene behind my door looked like the Titanic. The building was sinking! The marbles and walls were turning into pieces. Without shoes I sprinted through the hall and got outside. When I looked behind, I thought it was a miracle that my life was saved. I met my sister only in the evening that day. We both cried a lot holding each other. The next day I dreaded to go back. But I had to look for my stuff. I saw pieces of gifts from my friends and my collection of tiny memorabilia, things I had collected with love and passion. The only thing I found intact was an old sack of books. Now whenever I pass by my old home, my body shakes with fear.”

Rejina Bhattari | Kirtipur

‘I still expect to see the tower when I’m here’

Story: Sven Wolters

Photo: Sven Wolters

“Since I was a little boy I came up here to see the Dharahara tower. You could see the top half of it from here. Back then the public was not allowed to enter. I always wanted to go. A few years ago it finally opened. It was awesome. The stairways were really crazy. But the best part of it was the view from up there. You could see all of Kathmandu. When the earthquake happened I ran up here. I could not see anything. There was dust everywhere. I still expect to see the tower when I’m here. And the government said they will rebuild it right away. But nothing has happened. I don’t think it ever will. I had brought a piece of rubble from the tower, as a token, but my mother said it would only bring bad luck. So I threw it away.”

Vasisht Pradha | Kathmandu

‘I feel honoured to have the ability to help victims to reconstruct their houses’

Story: Sven Wolters

Photo: Sven Wolters

“Many earthquake victims think we cannot help them. But at this workshop for engineers we learnt how to build earthquake resilient houses from nothing but mud and stone. That is important because these are the local materials used in most villages. I feel honoured to have the ability to help victims to reconstruct their houses. When we go out there and they see how we can support them they are very grateful. And that is the best part of my job.”

Manja Khadka | Kathmandu

‘It has been a year now since the stadium had any games and matches’

Story: Pratik Rana

Photo: Sven Wolters

“This stadium is like a temple for us. I love this place. Now it looks deserted and that makes me feel sad. It has been a year now since the stadium had any games and matches. Before we used to have national football league. I don’t know if it’s the lack of cooperation or lack of money, but the government seems to be very slow and reconstruction is as it is. We give what it takes, we give all our sweat and blood, but when the government don’t meet your expectations it just makes you feel very low.”

Tej Bohara | Dasarath Rangasala Stadium, Kathmandu