By mid-afternoon, the celebrations came to a close. It was early, but the tracks across the hills were unlit and many needed to leave soon. A woman with a basket on her back picked up the sweet wrappers that the children had left. Men dismantled the sound system. Children swept the floor and helped to roll up the ground sheet.

I was staying the night with Pokharel. As we made our way down a steep, dark track to his hamlet, I noticed scenes of devastation. The pastor pointed out a small patch. Before the earthquake, six houses had stood here. Now all that remained was rubble and two shacks.

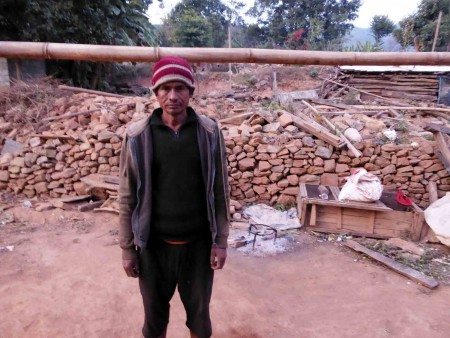

“Winter is so hard,” Sudarsan Khatri, who lived in one of the shacks. “This temporary home is no good. No insulation. It’s damp. We sleep at night and water drips on us.

Sudarsan Khatri. Photo: Patrick Ward

“We can’t rebuild because we don’t have the money. I don’t have much hope for the New Year.”

We couldn’t delay there too much. It was getting dark, and only mountain goats could work their way down this trail with any sense of ease. It took another 20 minutes of stumbling navigation before we emerged into a clearing, which housed several small shelters belonging to two families.

Pokharel’s shack appeared sturdy, with zinc sheets over a wooden frame. The main room doubled as the bedroom and living room and was kept as tidy as could be, considering the blurred boundary between the outside and indoors. It held three beds. Clothing hung from lines of strings tied across the rafters. There was an open kitchen area next to it.

The pastor shared the shack with his mother and his frail father, both of whom welcomed my intrusion with touching warmth, eager to share what they had with me, without reservation. Despite the language barrier, I was continuously corralled towards the warmest seat by the fire, invited to eat fresh-from-the-tree bananas, and handed metal cups of warm water to drink. The two words I heard frequently from Pokharel’s mother, which I did understand, were, “Hallelujah, dhanyavad!” [“Hallelujah, thank you!”].

Later, as night fell, we sat outside, under the giant leaves of a banana tree. Pokharel’s mother was cooking dinner outside. The pastor played Hindi songs on his mobile phone and we huddled there, around the open fire, against a backdrop of majestic hills and mountains, cloaked in mist and bathed in the light of a full moon. Yes, there was beauty, tranquillity, even amidst devastation.

Pokharel’s mother had prepared a traditional Nepali dinner for us—rice and potatoes with pickle—and we retired soon. I was given a bed to myself, and plied with warm blankets. I removed my thick coat; it was too much to sleep in. But I kept my woollen hat and gloves on and covered myself with blankets. It was still cold. The shelter had plenty of gaps through which the near-freezing Himalayan air drifted in. Pokharel’s father was sick, and the cold air could not be doing him any good. And there were hundreds, thousands, like him, caught in the cold, in the remote areas of the district. When would they receive the promised government help? Where did the NGOs go? Where will this family be next Christmas?

Many before me have written about the ‘resilience’ of the Nepali people, how they are brimming with it. Yes, there is resilience, but it is a resilience borne out of a lack of options. It is a reality that has been forced on them. It is, in essence, a question of survival. The only thing that appeared to be working for them, it seemed to me, was the way the community had rallied together. How people like Pokharel and Hingmang and Ramnanagar are doing what they can with the little they had.

“We don’t have the money,” Pokharel had said earlier. “But we have the heart.”